With amusement: Michael Blumenthal's farewell letter to his poetry writing students, which puts paid to much of the mushiness all too prevalent in creative writing programs.

And Stephen Budiansky's Times op-ed piece on the branding of American higher education.

***

An influx of bookage: from Jeff Twitchell (proprietor of the absolutely essential Z-Site for Zukofsky research) a bundle of recencies by J. H. Prynne, including the pamphlets (that's English for chapbooks) Acrylic Tips and Biting the Air, and a copy of the hard-to-find lectures Stars, Tigers and the Shapes of Words. I can't wait to read, once I get through this stack of papers.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the local used bookstore divulged a copy of the 1967 Pennant Key-Indexed Study Guide to Homer's The Odyssey, by Guy Davenport, Ph.D. I won't tell you what I paid; look it up on abe.books, and rest assured that what it cost me would make a bookseller weep. (That's okay – these good folks have gotten enough of my money in the past, & will get enough in the future.) I'm always fascinated by the spectacle of a really interesting writer taking on scutwork – LZ's Index of American Design writing, for instance, or Pound's music reviews. And this one even has the advantage of Guy's own drawings of Achaian armor & suchlike.

***

& the weekly random 10:

1) "Lathe of God," Painkiller, Guts of a Virgin

2) "Lanterns," Killing Joke, Democracy

3) "Hal-an-Tow," Oysterband, Trawler

4) "St. Valentine's Day," Mekons, I Love Mekons

5) "The River," Brian Eno

6) "Tincans," Oysterband, Ride

7) "Sixteen Dances X," John Cage

8) "Coney Island Baby," Tom Waits, Blood Money

9) "My Lady Careys Dompe," Philip Pickett with Richard Thompson, The Bones of All Men

10) "One of These Days," Velvet Underground, Gold

Saturday, April 29, 2006

Thursday, April 27, 2006

The home stretch

Okay, so now it's all over but the grading, which I was puttering at today as I nursed a hangover from last night's last meeting of my "Poetry & Theory" seminar. Now that was fun: I nattered on for a while trying futilely to tie together some of the ideas in play during the last few weeks of class, then we kicked back to watch the second half of The Ister, all well-lubricated by many bottles of wine, some choice Belgian cherry beer, and Pernod with Perrier. Very decadent. And then off to the local "English" pub, where we bemused various antipodean rugby-playing regulars by talking at great length about Celan and Heidegger.

The course, which I'd been contemplating for some time, didn't quite come off as I'd planned (tho of course they never do). I'd foreseen the whole thing pivoting as it were around the materialist readings I'd programmed towards the middle – Antony Easthope, Adorno, Bernstein – but it turned out that the Celan unit at the end (Celan, Szondi, Gadamer, Derrida, Lacoue-Labarthe) captured my own imagination (and evidently the imaginations of some of the seminar members) even more than I'd expected. "Primary" texts: "The Meridian," "Du liegst," "Todtnauberg," and a handful of other Celan poems and talks, read thru the progressive prisms of Szondi's "Eden" essay fragment, the afterword to Gadamer's Who Am I and Who Are You?, bits of Derrida's "Shibboleth," and Lacoue-Labarthe's Poetry as Experience. Key themes: the poem's occasion; the "date" inscribed in the poem; the poem as "dialogue," "message in a bottle"; the status of extratextual reference (in a poetry PC himself always insisted was "ganz und gar nicht hermetisch" – yeah, right).

As if we didn't have enough balls in play over the past few weeks, midway thru the semester I got a brand new book which threatened to play the "archival research trumps speculative theory" card: James K. Lyon's Paul Celan and Martin Heidegger: An Unresolved Conversation, 1951-1970 (Johns Hopkins UP, 2006).* I'm looking forward to the reviews and responses to this one, which goes a really long way towards undermining a reading of the poem "Todtnauberg" as a record of Celan's bitter disappointment with his 1967 meeting with Heidegger at the philosopher's Black Forest cabin at Todtnauberg. It's a record of the meeting, all right, but Lyon shows – in a manner which looks pretty damned scrupulous – that when the poem was written, six days after that meeting, Celan by all reports was on a Heidegger high: he wasn't disappointed at all by what MH had told him about his (MH's) involvement with the Nazis, nor was he bitter about MH's silence concerning the Holocaust; on the contrary, he appeared to be well pleased with what he'd gotten out of his face-time with Heidegger.

All this, of course, contra the received reading of "Todtnauberg" (cf. Lacoue-Labarthe, and Pierre Joris in various places, & lots of other people). It all appears to be a matter of various readers reading Celan's disappointment and bitterness – oh yes, he changed his mind about Heidegger, tho he never stopped reading him, and even met him a couple more times before his death – back into a poem which was written before that reaction set in, and which – on its face – seems to bear few marks of anything other than a dispassionate note-jotting about a serious and much-anticipated meeting.

But I'm convinced, even tho one might have to scrap a reading of "Todtnauberg" that attributes bitterness and disappointment to its original occasion – to find that "date" inscribed in that particular manner – that there's still a good deal of truth in Lacoue-Labarthe's assessment of the poem as "an extenuated poem, or, to put it better, a disappointed one. It is the poem of a disappointment; as such, it is, and it says, the disappointment of poetry." Somewhere percolating in the depths of my mind, and sparking among these various texts, is the material for a proleptic theory of poetry, in which the poem rises up to meet the conditions for its future reception. But it'll have to wait until I get thru all these papers.

*This is not a book I'd recommend either for its stylistic flourishes – none, on the contrary a kind of dogged, repetitive presentation of facts and documents – nor for its theoretical sophistication; but it is an example of the sort of strenuous (almost "Germanic"?) archival scholarship that's perhaps a bit too rare today.

The course, which I'd been contemplating for some time, didn't quite come off as I'd planned (tho of course they never do). I'd foreseen the whole thing pivoting as it were around the materialist readings I'd programmed towards the middle – Antony Easthope, Adorno, Bernstein – but it turned out that the Celan unit at the end (Celan, Szondi, Gadamer, Derrida, Lacoue-Labarthe) captured my own imagination (and evidently the imaginations of some of the seminar members) even more than I'd expected. "Primary" texts: "The Meridian," "Du liegst," "Todtnauberg," and a handful of other Celan poems and talks, read thru the progressive prisms of Szondi's "Eden" essay fragment, the afterword to Gadamer's Who Am I and Who Are You?, bits of Derrida's "Shibboleth," and Lacoue-Labarthe's Poetry as Experience. Key themes: the poem's occasion; the "date" inscribed in the poem; the poem as "dialogue," "message in a bottle"; the status of extratextual reference (in a poetry PC himself always insisted was "ganz und gar nicht hermetisch" – yeah, right).

As if we didn't have enough balls in play over the past few weeks, midway thru the semester I got a brand new book which threatened to play the "archival research trumps speculative theory" card: James K. Lyon's Paul Celan and Martin Heidegger: An Unresolved Conversation, 1951-1970 (Johns Hopkins UP, 2006).* I'm looking forward to the reviews and responses to this one, which goes a really long way towards undermining a reading of the poem "Todtnauberg" as a record of Celan's bitter disappointment with his 1967 meeting with Heidegger at the philosopher's Black Forest cabin at Todtnauberg. It's a record of the meeting, all right, but Lyon shows – in a manner which looks pretty damned scrupulous – that when the poem was written, six days after that meeting, Celan by all reports was on a Heidegger high: he wasn't disappointed at all by what MH had told him about his (MH's) involvement with the Nazis, nor was he bitter about MH's silence concerning the Holocaust; on the contrary, he appeared to be well pleased with what he'd gotten out of his face-time with Heidegger.

All this, of course, contra the received reading of "Todtnauberg" (cf. Lacoue-Labarthe, and Pierre Joris in various places, & lots of other people). It all appears to be a matter of various readers reading Celan's disappointment and bitterness – oh yes, he changed his mind about Heidegger, tho he never stopped reading him, and even met him a couple more times before his death – back into a poem which was written before that reaction set in, and which – on its face – seems to bear few marks of anything other than a dispassionate note-jotting about a serious and much-anticipated meeting.

But I'm convinced, even tho one might have to scrap a reading of "Todtnauberg" that attributes bitterness and disappointment to its original occasion – to find that "date" inscribed in that particular manner – that there's still a good deal of truth in Lacoue-Labarthe's assessment of the poem as "an extenuated poem, or, to put it better, a disappointed one. It is the poem of a disappointment; as such, it is, and it says, the disappointment of poetry." Somewhere percolating in the depths of my mind, and sparking among these various texts, is the material for a proleptic theory of poetry, in which the poem rises up to meet the conditions for its future reception. But it'll have to wait until I get thru all these papers.

*This is not a book I'd recommend either for its stylistic flourishes – none, on the contrary a kind of dogged, repetitive presentation of facts and documents – nor for its theoretical sophistication; but it is an example of the sort of strenuous (almost "Germanic"?) archival scholarship that's perhaps a bit too rare today.

Tuesday, April 25, 2006

Noted

Jane/Joshua's "Cut 'n' Paste Poetics Blogwar," which is almost too accurate to be funny.

***

Lori Jareo, a big Star Wars fan, has advertised her "non-canonical" print-on-demand SW novel, Another Hope, on Amazon.com; unfortunately, she never got around to asking the Lucas people for permission to write about their "universe." Cease and Desist orders have gone out.

I would say "ho-hum," with a bit of the raised eyebrow at the genre of "fan fiction," about which I knew precisely nothing before this crossed the radar screen, except for the fact that Jareo, it turns out, is also one of the proprietors of the WordTech Communications poetry publishing outfit, a POD unit that on its face seems to be making a good faith effort to provide a book outlet for poets who are entirely unplugged from the "scene." And she's published her Stars Wars thing, it seems, under the same imprint. Oh dear. Kids, remember the old school punk adage? If the labels won't bite, then DIY.

***

[Of interest only to academics – and those who don't want American universities entirely subcontracted out to WalMart and Halliburton:] An "issue paper" from the Department of Education on why college costs so much: it's the faculty, of course. Only room for a few choice morsels of this business-school produced piece o' crap:

Comments on this abomination on Inside Higher Ed and Michael Bérubé.

***

Lori Jareo, a big Star Wars fan, has advertised her "non-canonical" print-on-demand SW novel, Another Hope, on Amazon.com; unfortunately, she never got around to asking the Lucas people for permission to write about their "universe." Cease and Desist orders have gone out.

I would say "ho-hum," with a bit of the raised eyebrow at the genre of "fan fiction," about which I knew precisely nothing before this crossed the radar screen, except for the fact that Jareo, it turns out, is also one of the proprietors of the WordTech Communications poetry publishing outfit, a POD unit that on its face seems to be making a good faith effort to provide a book outlet for poets who are entirely unplugged from the "scene." And she's published her Stars Wars thing, it seems, under the same imprint. Oh dear. Kids, remember the old school punk adage? If the labels won't bite, then DIY.

***

[Of interest only to academics – and those who don't want American universities entirely subcontracted out to WalMart and Halliburton:] An "issue paper" from the Department of Education on why college costs so much: it's the faculty, of course. Only room for a few choice morsels of this business-school produced piece o' crap:

The time-honored practice of tenure is costly. Tenure was originally conceived as a means to protect “academic freedom.” [dig those scare quotes] It has evolved into a system to protect job security. A combination of institutional practice and emerging case law has resulted in a situation where institutional flexibility is reduced in two key ways. First, if student demand for academic programs shifts [of course, the life of the mind has always been demand-driven], faculty capacity to deliver it cannot. Tenured faculty members are not interchangeable parts (a physics professor can’t usually teach journalism, and vice versa). [duh]The ultimate solution? Scale universities back to internet-based vocational programs serving only the skills students demand the most in order to become happy, profit-making parts in the great industrial machine. No more tenure – those online courses can be taught entirely by adjuncts; no more physical libraries – after all, they can get any data they need on the internet; no more wasteful "research" "releases" for the folks chained to their keyboards grading exams.

Colleges are not managed with efficiency as the primary value. [where in God's name did this fellow get the idea that they should be?]

a. Colleges maintain large physical infrastructures that often include libraries, computing centers, academic and student-oriented buildings, power plants, research facilities, theatres and stadiums. This infrastructure is rarely used to capacity.

To understand the management of a college one must understand the unique culture and extraordinary power of the faculty. [Where does this guy teach? I want a job there!] To many faculty, they are the university. [I don't believe this, entirely: in my mind, the university is first its students; then its faculty; then the staff who support the teaching and research that goes on in the institution; I imagine I disagree with Robert Dickeson (the report's author) in seeing administration – what he calls "management" – as little more than a necessary evil. "That government governs best that governs least," said somebody wiser than either of us.] This tenet explains a number of practices that distinguish college management from most other forms of management. Among these practices are: the keen importance of process in undertaking decision-making on campus, a factor that explains the slow-moving pace of change that characterizes most institutions; the assumption that the faculty “own” all curricular decisions, and the concomitant reluctance to challenge that authority when meaningful reform is indicated

Comments on this abomination on Inside Higher Ed and Michael Bérubé.

Boxing Duchamp

In all my excitement over The Ister, I forgot to mention a new arrival in the household that will probably hold my attention much longer: an anniversary present, the big book Marcel Duchamp: The Box in a Valise (de ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Selavy): Inventory of an Edition, by Ecke Bonk (Rizzoli, 1989). I've always been fascinated by Duchamp, & convinced that his ideas about art probably have a lot of bearing on contemporary poetry. (For instance, his early and repeated rejection of "retinal art" – art that provides immediate sensual pleasure to the eye – in favor of an art of ideas, an art that appeals to the mind rather than the senses, is probably of some relevance to the discussion of the relationship between intellectuality and immediate apprehensibility in alt-poetry going on over on Josh Corey's blog these days.)

The Box in a Valise is an exhaustive and loving chronicle, with pictures and diagrams of every detail, of Duchamp's monumental-miniature "late" work, the Boîte-en-valise, a handy wooden carrying case containing reproductions – most of them made thru painstaking and enormously time-consuming handicraft methods – of all of his major works, and most of his minors. There's a wee clay model of "Fountain," the signed urinal; there are hand-colored reproductions of all of the paintings; there are precise simulacra of his odder projects (the fake checks, the Monte Carlo investment "bonds" Duchamp had made for his own attempt to break the bank at roulette; there are photos of most of the ready-mades).

It's an amazing, and amazingly obsessive project. It took Duchamp over five years of full-time labor to produce the reproductions of his works for the approximately 350 copies of the Box, and he would release the finished products in "homeopathic doses" of maybe 20 to 30 over the last 27 years of his life.

It's a gesture I really love: a pocket "canon," as it were, an artist assembling – on his own idiosyncratic terms – the sort of catalogue raissoné that most artists have to wait a lifetime to see published. Or perhaps I'm just drawn to it by my own longstanding obsession with miniaturization, with shrinking the big down into the little. Zukofsky claims somewhere that 80 Flowers – a book that totals 648 lines of verse – was the compact version of his entire life's work. Something to be said for shriking it all down into something you can tuck under an arm and walk away with. Thoreau would approve.

Saturday, April 22, 2006

But what do you compare it to?

Couple days ago I told Jessica Smith that I wasn’t kidding when I said (of Annie Finch) “I love it when people talk of poetry as a dance”: “I always remember – tho I can't lay my finger on it” (said I) “that passage where WCW kicks Pound's butt over the ‘condition of music’ business, and tells him that if poetry has to be compared to anything, it ought to be compared to dancing.” So Michael Zbigley replies:

I don't deny the historical linkage of music & poetry, & EP, Zukofsky, and Bunting among others certainly got a lot of mileage out of the entertwined roots of the two arts. But for all the maddening & wonderful inconsistencies of WCW's statements about poetics, I think he's onto something: that the Paterian notion of art aspiring to a "condition of music" – a content-free, non-referential, purely formal shape – is only one of the options open to the poet in the 20th century & beyond.

Admittedly, there is a very basic pleasure to be obtained from the poet with a conventionally or unconventionally musical ear. And one can't gainsay the achievements of poets who've been attracted by the model of music – Pound and Zukofsky, to name 2 who really didn't know jack about music in any substantial sense, and Bunting, who seems to have known quite a bit. But there's no meaningful, foundational link between the two arts – maybe never, and not anymore if there ever was.

I find, as I get older and even dorkier on the dance floor than I was when I was young & thin, that I find the metaphor of dance – and metaphors're all they are, these "musics" and "dances" and "paintings," after all? – more attractive when I sit down to write. Celan's "Todesfuge" got analyzed in German high school classes all thru the '70s for its "fugal form," but it's worth remembering that the poem started life as "Todestango."

***

Oh yes, the weekly random 10:

1) “Den of Sins,” Naked City, Naked City

2) “Born to Run,” Emmylou Harris, Spyboy

3) “Down Where the Drunkards Roll,” Richard Thompson, the big box set

4) “Bottle of Smoke,” The Pogues, If I Should Fall from Grace with God

5) “I Don’t Know,” Mekons, I Love Mekons

6) “Friendly Ghosts,” Mark Ribot, Rootless Cosmopolitans

7) “Archimedes,” John Cale, Hobo Sapiens

8) “Garage d’Or,” Mekons, Original Sin

9) “Long Dark Street,” Oysterband, The Shouting End of Life

10) “Ashes to Ashes,” David Bowie, Scary Monsters

Pound also said "Music rots when it gets too far from the dance. Poetry atrophies when it gets too far from music."Well, I found the WCW passage I had in mind, from towards the end of Spring and All:

I don't recall that WCW line, but I suppose the salient point is that both dance and poetry arose as responses to music, supplements, you might say.

The Derridean logic of the supplement certainly plays out in poetry's history, i.e. poetry as augmentation to music becomes poetry as replacement for music, but this seems less apt for dance. I suppose purveyors of modern dance see their work as separable from music just as poets since at least the 13th century have been happy to speak their poems sans melody.

Pound again: "There are three kinds of melopoeia, that is, verse made to sing; to chant or intone; & to speak. The older one gets the more one believes in the first."

Writing is likened to music. The object would be it seems to make poetry a pure art, like music. Painting too. Writing, as with certain of the modern Russians whose work I have seen, would use unoriented sounds in place of conventional words. The poem would then be completely liberated when there is identity of sound with something – perhaps the emotion.Nothing about dance there, tho my memory isn't playing me entirely false, since Wms a few lines before writes of how poetry "creates a new object, a play, a dance which is not a mirror up to nature but –"

I do not believe that writing is music. I do not believe writing would gain in quality or force by seeking to attain to the conditions of music. (Imaginations 150)

I don't deny the historical linkage of music & poetry, & EP, Zukofsky, and Bunting among others certainly got a lot of mileage out of the entertwined roots of the two arts. But for all the maddening & wonderful inconsistencies of WCW's statements about poetics, I think he's onto something: that the Paterian notion of art aspiring to a "condition of music" – a content-free, non-referential, purely formal shape – is only one of the options open to the poet in the 20th century & beyond.

Admittedly, there is a very basic pleasure to be obtained from the poet with a conventionally or unconventionally musical ear. And one can't gainsay the achievements of poets who've been attracted by the model of music – Pound and Zukofsky, to name 2 who really didn't know jack about music in any substantial sense, and Bunting, who seems to have known quite a bit. But there's no meaningful, foundational link between the two arts – maybe never, and not anymore if there ever was.

I find, as I get older and even dorkier on the dance floor than I was when I was young & thin, that I find the metaphor of dance – and metaphors're all they are, these "musics" and "dances" and "paintings," after all? – more attractive when I sit down to write. Celan's "Todesfuge" got analyzed in German high school classes all thru the '70s for its "fugal form," but it's worth remembering that the poem started life as "Todestango."

***

Oh yes, the weekly random 10:

1) “Den of Sins,” Naked City, Naked City

2) “Born to Run,” Emmylou Harris, Spyboy

3) “Down Where the Drunkards Roll,” Richard Thompson, the big box set

4) “Bottle of Smoke,” The Pogues, If I Should Fall from Grace with God

5) “I Don’t Know,” Mekons, I Love Mekons

6) “Friendly Ghosts,” Mark Ribot, Rootless Cosmopolitans

7) “Archimedes,” John Cale, Hobo Sapiens

8) “Garage d’Or,” Mekons, Original Sin

9) “Long Dark Street,” Oysterband, The Shouting End of Life

10) “Ashes to Ashes,” David Bowie, Scary Monsters

Thursday, April 20, 2006

Honey, get the kids out of the house...now!

And this sighted in Friday's Washington Post:

Learning the Wrong Things From Poetry

Fill your house with books if you want little Billy or Beth to grow up to be an academic all-star. Shakespeare is good. But stay away from poetry -- books of poesy on your shelves may dumb down your child.

A research team headed by demographer Jonathan Kelley, of Brown University and the University of Melbourne, analyzed data from a study of scholastic ability in 43 countries, including the United States. The data included scores on a standardized achievement test in 2000 and detailed information that parents provided about the family. The average student scored 500 on this test.

The researchers found that a child from a family having 500 books at home scored, on average, 112 points higher on the achievement test than one from an otherwise identical family having only one book -- and that's after they factored in parents' education, occupation, income and other things typically associated with a child's academic performance. The findings were presented last month at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America in Los Angeles.

Of course, it's not the number of books in the home that boosts student performance -- it's what they represent. The researchers say a big home library reflects the parents' dedication to the life of the mind, which probably nurtures scholastic accomplishment in their offspring.

They also found that not all books are created equal. "Having Shakespeare or similar highbrow books about bodes well for children's achievement," they wrote. "Having poetry books around is actively harmful by about the same amount," perhaps because it signals a "Bohemian" lifestyle that may encourage kids to become guitar-strumming, poetry-reading dreamers.

Learning the Wrong Things From Poetry

Fill your house with books if you want little Billy or Beth to grow up to be an academic all-star. Shakespeare is good. But stay away from poetry -- books of poesy on your shelves may dumb down your child.

A research team headed by demographer Jonathan Kelley, of Brown University and the University of Melbourne, analyzed data from a study of scholastic ability in 43 countries, including the United States. The data included scores on a standardized achievement test in 2000 and detailed information that parents provided about the family. The average student scored 500 on this test.

The researchers found that a child from a family having 500 books at home scored, on average, 112 points higher on the achievement test than one from an otherwise identical family having only one book -- and that's after they factored in parents' education, occupation, income and other things typically associated with a child's academic performance. The findings were presented last month at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America in Los Angeles.

Of course, it's not the number of books in the home that boosts student performance -- it's what they represent. The researchers say a big home library reflects the parents' dedication to the life of the mind, which probably nurtures scholastic accomplishment in their offspring.

They also found that not all books are created equal. "Having Shakespeare or similar highbrow books about bodes well for children's achievement," they wrote. "Having poetry books around is actively harmful by about the same amount," perhaps because it signals a "Bohemian" lifestyle that may encourage kids to become guitar-strumming, poetry-reading dreamers.

Various

The latest heartwarming photo-op from the White House: "Katrina Kids" shivering on the lawn at the annual Easter Egg Roll, serenading the First Lady to the tune of "Hey Look Me Over":

***

From the "Never Underestimate a Slacker Undergrad" department: Today in my Am Lit course we were doing some Dickinson poems, in particular Johnson #1052:

***

I have – to the detriment of my work, my family life, and my sleep schedule – finished watching The Ister; and I pronounce it good. Very good indeed. Don't miss the extra 25 minute bonus segment of Werner Hamacher extemporizing on Heidegger's reading of Hölderlin; I wish I could talk like that. (I wish I was that good looking!)

***

Oh indeed, Jessica, no irony about poetry as dance. I always remember – tho I can't lay my finger on it – that passage where WCW kicks Pound's butt over the "condition of music" business, and tells him that if poetry has to be compared to anything, it ought to be compared to dancing. (Dylan Thomas to Harry Levin, upon being introduced to Levin & told he was a professor of Comparative Literature: "And what do you compare it to?")

***

J. leaves tomorrow for another weekend at the Folger in Washington, thus casting me into single parent status. Survival is probable, tho not assured.

Our country’s stood beside usI know I'm moved – or at least bits of my digestive system are in motion.

People have sent us aid.

Katrina could not stop us, our hopes will never fade.

Congress, Bush and FEMA

People across our land

Together have come to rebuild us and we join them hand-in-hand!

***

From the "Never Underestimate a Slacker Undergrad" department: Today in my Am Lit course we were doing some Dickinson poems, in particular Johnson #1052:

I never saw a Moor –The first question – I'm not making this up – was "What's Heather?" To which someone replied – and I'm not making this up either, nor was he joking – "It's a girl's name."

I never saw the Sea –

Yet know I how the Heather looks

And what a Billow be.

***

I have – to the detriment of my work, my family life, and my sleep schedule – finished watching The Ister; and I pronounce it good. Very good indeed. Don't miss the extra 25 minute bonus segment of Werner Hamacher extemporizing on Heidegger's reading of Hölderlin; I wish I could talk like that. (I wish I was that good looking!)

***

Oh indeed, Jessica, no irony about poetry as dance. I always remember – tho I can't lay my finger on it – that passage where WCW kicks Pound's butt over the "condition of music" business, and tells him that if poetry has to be compared to anything, it ought to be compared to dancing. (Dylan Thomas to Harry Levin, upon being introduced to Levin & told he was a professor of Comparative Literature: "And what do you compare it to?")

***

J. leaves tomorrow for another weekend at the Folger in Washington, thus casting me into single parent status. Survival is probable, tho not assured.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

The Ister

What a gift! One of my (soon-to-be-ex-) students somehow managed to wangle me – apparently by way of India and other points east – a DVD copy of David Barison and Daniel Ross's monumental film The Ister. (I shan't name my benefactor, since I'm not entirely sure of the legality of this transaction, the film as yet not being available in the US at a price anybody short of a major research library could afford. Suffice it to say I've spent a bit of time downloading software to enable me to get around "region codings.")

On its face, this seems an unlikely project: a three-hour film that travels 3000 kilometers up the Danube, from its mouth to its source, all loosely organized around Martin Heidegger's 1942 lecture series on Hölderlin's hymn "The Ister" (the ancient name for the river). It's philosophy lesson as travelogue, long static shots of the river and surrounding towns accompanied by off-the-cuff lectures by French luminaries Bernard Stiegler, Jean-Luc Nancy, and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe (as well as German filmmaker Hans-Jürgen Syderberg). Along the way we tour the whole postwar history of Europe, from the fall of the Iron Curtain to the wars in the former Yugoslavia, all converging on Heidegger, Hölderlin, the legacy of the ancient Greeks, and the Third Reich.

Okay, I'll confess: I haven't screened the whole movie yet; on the other hand, I've had a great deal of trouble tearing myself away from it to do such mundane things as prepare lectures and read course text. But it certainly beats the Derrida film hands down, as far as cinematic versions of contemporary philosophy go. And it's a very beautiful film indeed, paced as slowly as Tarkovski (it's not surprising that Barison turned to making films specifically after seeing Tarkovski's The Mirror), yet full of haunting details. I have some problems with listening to philosophers improvising – Bernard Stiegler, for instance, recaps much of Technics and Time I: The Fault of Epimetheus in talk that is far less snappy than his prose – but on the other hand, it's worth it to hear the occasional squawks of his little girl in the background & see the opening and shutting of kitchen cabinets behind his work table.

Lacoue-Labarthe is quite rivetting, even beyond the painful game of wondering when exactly he's going to light the cigarette he keeps gesticulating with. He's afraid, it seems, that he's been too easy on Heidegger in the past, too light on the philosopher's involvement with the Nazis & too light on his refusal to comment on Auschwitz. Lacoue-Labarthe's discussion of Heidegger, of the "caesura" in history the Holocaust marks, and of Paul Celan's term "Atemwende," all of which floats over a montage of images from one of the death camps, is astonishing.

Clearly this film was a labor of love, & I hate to undercut whatever sales it might have in the States – if, that is, it ever gets released commercially; but I don't blame anyone else who wants to phone up a friend overseas and start figuring out how to circumvent the region codes on their DVD player. The Ister is definitely worth it.

Friday, April 14, 2006

sightings

La poésie in the news: the Times runs a story on the "fib," a Fibonacci Series-based form that's set to replace the haiku in the hearts of junior-high teachers and poetically-inclined Dan Brown readers. Dig that measured quotation from Annie Finch: "The form gives you something to dance with so it's not just you alone on the page." I love it when people talk of poetry as a dance.

***

In Reno, a federal judge has ruled that a ninth-grader will be allowed to recite Auden's "The More Loving One" in a state competition, even tho the poem contains the words (horrors!) "hell" and "damn." The dean of the student's charter school Cheryl Garlock, believes that the school should only present its students with "pristine" language.

***

Michel Foucault: "if I had encountered the Frankfurt School while young, I would have been seduced to the point of doing nothing else in life but the job of commenting on them. Instead, their influence on me remains retrospective, a contribution reached when I was no longer at the age of intellectual 'discoveries.'"

***

...& the weekly random 10:

1) Hüsker Dü, "Somewhere," Zen Arcade

2) French, Frith, Kaiser, Thompson, "A Blind Step Away," Live, Love, Larf and Loaf

3) Public Image Ltd., "Bad Baby," Second Edition

4) Brian Eno, "Decentre," Nerve Net

5) Pixies, "Nimrod's Son," Come On Pilgrim

6) U2, "Until the End of the World," Achtung Baby

7) Naked City, "Snagglepuss," Naked City

8) Mekons, "Slightly South of the Border," Original Sin

9) Pharoah Sanders, "Morning Prayer," Thembi

10) Gang of Four, "I Absolve You," Shrinkwrapped

***

In Reno, a federal judge has ruled that a ninth-grader will be allowed to recite Auden's "The More Loving One" in a state competition, even tho the poem contains the words (horrors!) "hell" and "damn." The dean of the student's charter school Cheryl Garlock, believes that the school should only present its students with "pristine" language.

***

Michel Foucault: "if I had encountered the Frankfurt School while young, I would have been seduced to the point of doing nothing else in life but the job of commenting on them. Instead, their influence on me remains retrospective, a contribution reached when I was no longer at the age of intellectual 'discoveries.'"

***

...& the weekly random 10:

1) Hüsker Dü, "Somewhere," Zen Arcade

2) French, Frith, Kaiser, Thompson, "A Blind Step Away," Live, Love, Larf and Loaf

3) Public Image Ltd., "Bad Baby," Second Edition

4) Brian Eno, "Decentre," Nerve Net

5) Pixies, "Nimrod's Son," Come On Pilgrim

6) U2, "Until the End of the World," Achtung Baby

7) Naked City, "Snagglepuss," Naked City

8) Mekons, "Slightly South of the Border," Original Sin

9) Pharoah Sanders, "Morning Prayer," Thembi

10) Gang of Four, "I Absolve You," Shrinkwrapped

Thursday, April 13, 2006

hi out there

It's been a way busy week. Lots of reading, lots of thinking, lots of teaching – not much writing, for whatever that's worth.

***

Everyone should go visit the really big sale at the University of California Press. I just got a big box from them, with poetry by Juliana Spahr, Martha Ronk, Srinkanth Reddy, Frank O'Hara, etc., and lots of other cool stuff I don't really have space for. And the packing peanuts in the box are actually edible – spray them with salt and they'd probably be as good as rice cakes.

One of the items: Pierre Joris's edition of Paul Celan: Selections; a really handy compilation, unfortunate only in its lack of German texts. The list of translators is telling: Pierre himself, Norma Cole, Cid Corman, Robert Kelly, Joachim Neugroschel, Jerome Rothenberg, Rosmarie Waldrop. Who's missing? Most notably, Michael Hamburger and John Felstiner. Two "schools" of Celan translators evident, I think.

***

Picking away at Antonia Fraser's Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot. Not the first account of the plot I'd read, but the first that takes an emphatically sympathetic Catholic stance.

***

Working towards a more positive personal presentation: less knee-jerk cynicism, more thoughtfulness. Finding a spot on the spectrum closer to the Ithaca Josh C than to the Berkeley Josh C. Brighten the corner where you are.

***

Everyone should go visit the really big sale at the University of California Press. I just got a big box from them, with poetry by Juliana Spahr, Martha Ronk, Srinkanth Reddy, Frank O'Hara, etc., and lots of other cool stuff I don't really have space for. And the packing peanuts in the box are actually edible – spray them with salt and they'd probably be as good as rice cakes.

One of the items: Pierre Joris's edition of Paul Celan: Selections; a really handy compilation, unfortunate only in its lack of German texts. The list of translators is telling: Pierre himself, Norma Cole, Cid Corman, Robert Kelly, Joachim Neugroschel, Jerome Rothenberg, Rosmarie Waldrop. Who's missing? Most notably, Michael Hamburger and John Felstiner. Two "schools" of Celan translators evident, I think.

***

Picking away at Antonia Fraser's Faith and Treason: The Story of the Gunpowder Plot. Not the first account of the plot I'd read, but the first that takes an emphatically sympathetic Catholic stance.

***

Working towards a more positive personal presentation: less knee-jerk cynicism, more thoughtfulness. Finding a spot on the spectrum closer to the Ithaca Josh C than to the Berkeley Josh C. Brighten the corner where you are.

Friday, April 07, 2006

The Crunch

We're still three weeks from the end of the semester, & I feel very much in the crunch. For one thing, it's MFA thesis defense season around Our University, and a couple of folks on whose committees I sit are winding up their projects right now. A very excellent poetry defense out of the way earlier this week, but early next week there's a novel that has to be defended – which means that there's a novel I need to be able to ask intelligent questions about, & to have read carefully. Nothing wrong with fiction, mind you – I just resent how much longer the form tends to be.

***

Weekly Random 10 (with lone classical movements deleted):

1) "Pop Tones," Public Image Ltd., Paris au Printemps

2) "Hard to be Human," Mekons, Heaven & Hell

3) "Heartbreak Hotel," John Cale, Slow Dazzle

4) "Healthy Colours III," Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, The Essential Fripp & Eno

5) "Notre Dame De L'Oubli (For Olivier Messiaen)," Naked City, Absinthe

6) "Midnight Jam," Joe Strummer & the Mescaleros, Streetcore

7) "Foreign Accents," Robert Wyatt, Cuckooland

8) "My Songbird," Emmylou Harris, Spyboy

9) "Sunday," Sonic Youth, A Thousand Leaves

10) "Orphan Train," Julie Miller, Broken Things

***

Weekly Random 10 (with lone classical movements deleted):

1) "Pop Tones," Public Image Ltd., Paris au Printemps

2) "Hard to be Human," Mekons, Heaven & Hell

3) "Heartbreak Hotel," John Cale, Slow Dazzle

4) "Healthy Colours III," Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, The Essential Fripp & Eno

5) "Notre Dame De L'Oubli (For Olivier Messiaen)," Naked City, Absinthe

6) "Midnight Jam," Joe Strummer & the Mescaleros, Streetcore

7) "Foreign Accents," Robert Wyatt, Cuckooland

8) "My Songbird," Emmylou Harris, Spyboy

9) "Sunday," Sonic Youth, A Thousand Leaves

10) "Orphan Train," Julie Miller, Broken Things

Go Thou & Buy

Michael Peverett pointed out a "Freudian slit" in that last post – "Barry Lydon," merging Ryan O'Neal and Johnny Rotten. I only wish I knew enough Photoshop to post a picture of the 18th-centurified O'Neal with a spiky Lydon quiff. Michael also asks whether I'll be reflecting "here on what sense there is to be made of a post-Zukofskyan tradition with an ambiguous pull towards closed forms?" I take it he refers to some of the remarks in Ron Silliman's recent take on Zach Barocas's Among Other Things, where Ron holds up LZ as a master of anal retentiveness. Aside from my own exasperated comments on that post, and a nice bit of reflection from Curtis Faville –

But not now. Right now I just want to celebrate the release of the latest volume in the Library of America's American Poets Project, Louis Zukofsky's Selected Poems edited by Charles Bernstein. Hurrah! This ain't Robert Pinsky's Williams, either, but a full-scale selection of the greatest LZ hits from one of the sharpest set of eyes in the field. You got a big selection of the short poems, you got 9 of the Flowers, you got 70 pages of "A" (including all of "A"-23), you got a handful of Cats, you got more than enough to teach an undergraduate semester or to persuade your stick-in-the-mud sweetie that this guy really is the shit! Everybody go buy this thing! Now! You! – yes, you, Carruthers! There in the back – you're not buying, young man!

And the first review seems to have hit the street, from of all places the Forward, where David Kaufmann makes a number of nifty observations, among them:

There's no question Zukofsky was meticulous. However that may have been expressed in his life--some couples live lives of scrupulous attention to detail. But the life of the mind is endlessly complex, and not to be measured in such terms. Poetry likewise. I never read an LZ poem without feeling his puckish mischief--there's always a sweet comedy or (contrarily) a dourness lurking between the lines. Good God!, read the Catullus--how could anyone without a sense of the absurdity and delight of accident (and gratuitous convergence) have composed such work???– yes, I think I'd like to think about Michael's suggestion in public.

But not now. Right now I just want to celebrate the release of the latest volume in the Library of America's American Poets Project, Louis Zukofsky's Selected Poems edited by Charles Bernstein. Hurrah! This ain't Robert Pinsky's Williams, either, but a full-scale selection of the greatest LZ hits from one of the sharpest set of eyes in the field. You got a big selection of the short poems, you got 9 of the Flowers, you got 70 pages of "A" (including all of "A"-23), you got a handful of Cats, you got more than enough to teach an undergraduate semester or to persuade your stick-in-the-mud sweetie that this guy really is the shit! Everybody go buy this thing! Now! You! – yes, you, Carruthers! There in the back – you're not buying, young man!

And the first review seems to have hit the street, from of all places the Forward, where David Kaufmann makes a number of nifty observations, among them:

There may be, of course, a touch of the parvenu's pushiness in Zukofsky's deep and vigorous play, a desire to show that he can indeed better the instruction of his (goyish) instructors and twist red-hot pokers into even more complicated knots. But his work, with its emphasis on puns, on different shades of sound and sense, has something of rabbinic argument, of pilpul, to it. Zukofsky's delight in sheer virtuosity and in naked displays of intelligence owes more than a little to this tradition.

Wednesday, April 05, 2006

Winstanley (1975)

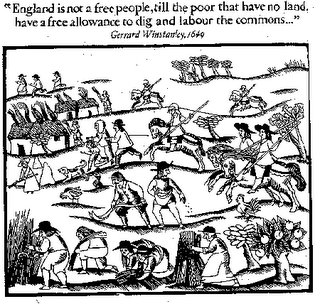

The four or five people out there who read my Anarchy know that I have a bit of an obsession with 17th-century British history, in particular in the intersection of orthodox and heterodox Christian beliefs and radical political movements. I am also happy to admit that I love historical costume-dramas, from Ken Hughes's broad-brush potboiler Cromwell (1970), to James Clavell's intriguing but deeply flawed Thirty Years' War flick The Last Valley (1971) – and not excepting Stanley Kubrick's near-static take on Thackeray's Barry Lyndon (1975). They must all now bow down in my personal pantheon to Kevin Brownlow's low-budget 1975 masterpiece Winstanley.

Gerrard Winstanley (1609-1676) was a radical pamphleteer during the Civil War period (along with about 50,000 others, it seems), a man with an argument: that the Lord had created the land as "a common treasury for all," that social subordination was contrary to God's intention for humanity: "in the beginning of time God made the earth. Not one word was spoken at the beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another, but selfish imaginations did set up one man to teach and rule over another." In 1649, the year of King Charles's beheading and the final triumph of Parliament's revolution, Winstanley led a small group of followers to "common" land on St. George's Hill, Surrey, where they established a small egalitarian agricultural colony that they hoped would be self-sustaining, beyond the necessity for buying, selling, and subordinating themselves to market logic and market hierarchies. In short, a proto-hippie socialist commune. It didn't last, of course: the "Diggers" (or "true Levellers"), as Winstanley's group was known, were driven off of the "commons" – lands technically reserved for cattle grazing, and off-limits for agriculture or wood-cutting – by forces of the local landowners.

By the late 1960s, when the very young Kevin Brownlow started work on Winstanley, his second film, the radical elements of the English Revolution were very much in the air among the British Left. (And here's a difference between the British and American Leftist traditions that intrigues me: unlike the Americans, the British can lay claim to a very venerable radical tradition indeed, one that's deeply intertwined with the tradition of religious dissidence – one that by some accounts goes as far back as the indigenous resistance to the Norman Conquest.) In 1972 the great Marxist historian Christopher Hill published his The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution, a volume that works very explicitly to establish a 17th-century intellectual pedigree for the student movement and other contemporary Leftist causes. (For very late Hill on Winstanley, see here.)

Brownlow's Winstanley is the diametric opposite of Hughes's Cromwell. The latter film was packed with color and expensive costuming and jammed with big stars – Alec Guinness as King Charles, Richard Harris as Cromwell, a very young Timothy Dalton as Prince Rupert. Hughes shot his film in black and white; the only real "actor" in Winstanley was Jerome Willis as General Fairfax, all of the other roles being taken by amateurs (for the most part an inspired stroke – for the film's band of "Ranters," Brownlow enlisted a party of contemporary hippie commune-dwellers who considered themselves the new Diggers); and while Brownlow's overall budget was something short of what it cost to film the opening credits for the latest James Bond feature, he went to absurd lengths to ensure the authenticity of his costumes, props, and scenes (in this rather like Kubrick in Barry Lyndon).

One way of conceiving Winstanley is to think of Barry Lydon's visual beauty and deliberate pace, distended (stripped of sumptuous soundtrack music, the long shots even more protracted) or Beckettesquely minimalized (no color, no more beautiful people – Brownlow's actors are remarkably real – dirty, shabby, unshaven, bad-toothed), and animated thruout by the stately rhythms of 17th-century English prose & the luminous power of Winstanley's ideas. At times – really very magical moments – one forgets that one is watching "fiction," the power of Brownlow's cinematography is so compelling, and one is convinced that one is watching an anthropological documentary filmed, by some species of necromancy, on a hill in Surrey in 1649. Unforgettable.

Monday, April 03, 2006

Pop Quiz

Which of the following three paragraphs might be published in the New York Times Book Review?

It's one thing – tho still flatulent hyperbole, & an astonishing dumbing-down of waves of subtle new historicist theorizing – for Harold Bloom to claim that Shakespeare "created" Western subjectivity. Goethe, Keats, and a number of other serious types would more or less agree. But by what excess of closeted subjectivity can one claim that Bishop – a fine and subtle poet at her best, but overshadowed in her own half-century by a range of American talents* that bears comparison to the most densely-crowded literary period you'd care to name – has "created" anything more than the template for 20 years' worth of unambitious magazine verse: the Fireside Poets of the second half of the century?

*Off the top of one's head, one notes that Bishop shared her American half-century with Louis Zukofsky, George Oppen, Lorine Niedecker, Jackson Mac Low, Kenneth Rexroth, Susan Howe, Lyn Hejinian, Ronald Johnson, Michael Palmer, Jay Wright, John Peck, Fanny Howe, etc. Generate your own list at your leisure; Jim Behrle needs to adapt the old Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover of the world as seen from Manhattan, so that it reflects the New Yorker's vision of poetry.

1) You are living in a world created by Andy Warhol. Granted, our culture owes its shape to plenty of other forces — Hollywood, Microsoft, Rachael Ray — but nothing matches the impact of a great artist, and in the second half of the 20th century, no American artist in any medium was greater than Warhol (1928-87). That he worked in one of our country's least popular fields, easel painting, doesn't matter. That he was the child of Slovakian immigrants doesn't matter. That he was gay doesn't matter. That he was addicted to various drugs, besotted with celebrity, and deeply eccentric — none of this matters. What matters is that he left behind a body of work that teaches us, as Italo Calvino once said of art generally, "a method subtle and flexible enough to be the same thing as an absence of any method whatever."Okay, you already know that #3 is the opening paragraph of David Orr's review of Bishop's Edgar Allan Poe & the Juke-Box, and that it's attracted all sorts of vitriol in the alt-poetry corner of the blogosphere (my favorite moment being Jonathan Mayhew's near-apopleptic fit). But the point of the pop quiz is not to demonstrate Times imbecility (for my money, Coltrane is clearly the "greatest" figure of these three, & if anyone's "created" the world we live in, that dubious honor goes most closely to Warhol), but to remark in what a very odd vocabulary they choose to couch their highest praise.

2) You are living in a world created by John Coltrane. Granted, our culture owes its shape to plenty of other forces — Hollywood, Microsoft, Rachael Ray — but nothing matches the impact of a great artist, and in the second half of the 20th century, no American artist in any medium was greater than Coltrane (1926-67). That he worked in one of our country's least popular fields, jazz, doesn't matter. That he was an African American doesn't matter. That his playing charted new reaches of abrasiveness doesn't matter. That he struggled with drugs and found solace in various mysticisms — none of this matters. What matters is that he left behind a body of work that teaches us, as Italo Calvino once said of music generally, "a method subtle and flexible enough to be the same thing as an absence of any method whatever."

3) You are living in a world created by Elizabeth Bishop. Granted, our culture owes its shape to plenty of other forces — Hollywood, Microsoft, Rachael Ray — but nothing matches the impact of a great artist, and in the second half of the 20th century, no American artist in any medium was greater than Bishop (1911-79). That she worked in one of our country's least popular fields, poetry, doesn't matter. That she was a woman doesn't matter. That she was gay doesn't matter. That she was an alcoholic, an expatriate and essentially an orphan — none of this matters. What matters is that she left behind a body of work that teaches us, as Italo Calvino once said of literature generally, "a method subtle and flexible enough to be the same thing as an absence of any method whatever."

It's one thing – tho still flatulent hyperbole, & an astonishing dumbing-down of waves of subtle new historicist theorizing – for Harold Bloom to claim that Shakespeare "created" Western subjectivity. Goethe, Keats, and a number of other serious types would more or less agree. But by what excess of closeted subjectivity can one claim that Bishop – a fine and subtle poet at her best, but overshadowed in her own half-century by a range of American talents* that bears comparison to the most densely-crowded literary period you'd care to name – has "created" anything more than the template for 20 years' worth of unambitious magazine verse: the Fireside Poets of the second half of the century?

*Off the top of one's head, one notes that Bishop shared her American half-century with Louis Zukofsky, George Oppen, Lorine Niedecker, Jackson Mac Low, Kenneth Rexroth, Susan Howe, Lyn Hejinian, Ronald Johnson, Michael Palmer, Jay Wright, John Peck, Fanny Howe, etc. Generate your own list at your leisure; Jim Behrle needs to adapt the old Saul Steinberg New Yorker cover of the world as seen from Manhattan, so that it reflects the New Yorker's vision of poetry.

Saturday, April 01, 2006

weekly random 10

I thought briefly of doing an April Fool's post, but then reflected on how sadistic most April foolery really is. Or maybe I've just been impressed by a recent Parents magazine feature on supposedly funny pranks dads had played on their preschoolers – fun stuff like freezing the milk & cereal overnight before serving them their breakfast, or gluing scattered spare change on the front walk and chortling as the wee tykes tried to fingernail the coins up.

Instead, I thought I'd start imitating a colleague's weekly random 10: set iTunes or the iPod (or whatever playback device one prefers) on "random" mode, & transcribe the first ten things that play. So today's:

1) "My Lady Carey's Dompe," Philip Pickett with Richard Thompson, The Bones of All Men

2) "Still Water," Daniel Lanois, Acadie

3) "Lovely Day," Pixies, Trompe Le Monde

4) "Shot in the Dark," Naked City, Live at the Knitting Factory

5) "Socialist," Public Image Ltd., Second Edition

6) "Sonata No. 2 for Violin & Piano: Larghissimo espressivo," Armin Loos, Zukofsky/Torre [those classical pieces sure have a way of breaking up the "party" of "party shuffle"]

7) "The Letter," Mekons, Edge of the World

8) "A Pair of Brown Eyes," Pogues, Rum, Sodomy, & the Lash

9) "Lantern Marsh," Brian Eno, Ambient 4/On Land

10) "Café Royal," Henry Cow, Concerts

Instead, I thought I'd start imitating a colleague's weekly random 10: set iTunes or the iPod (or whatever playback device one prefers) on "random" mode, & transcribe the first ten things that play. So today's:

1) "My Lady Carey's Dompe," Philip Pickett with Richard Thompson, The Bones of All Men

2) "Still Water," Daniel Lanois, Acadie

3) "Lovely Day," Pixies, Trompe Le Monde

4) "Shot in the Dark," Naked City, Live at the Knitting Factory

5) "Socialist," Public Image Ltd., Second Edition

6) "Sonata No. 2 for Violin & Piano: Larghissimo espressivo," Armin Loos, Zukofsky/Torre [those classical pieces sure have a way of breaking up the "party" of "party shuffle"]

7) "The Letter," Mekons, Edge of the World

8) "A Pair of Brown Eyes," Pogues, Rum, Sodomy, & the Lash

9) "Lantern Marsh," Brian Eno, Ambient 4/On Land

10) "Café Royal," Henry Cow, Concerts

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)