There's an interesting moment in the final "Note" to Ronald Johnson's complete ARK (1996), where he speaks of the influences on his own long poem: "Zukofsky and Olson, braving new schemes for language – The Minimalist and The Maximus – such opposing poles of influence: parities." Johnson's not the only poet of his generation for whom CO (born 1910) and LZ (1904) seem to offer contrary but equally attractive paths; Robert Creeley and Robert Duncan would both speak of Olson and Zukofsky as personal lodestones, and there are bunches of others one could name – Robert Kelly, Theodore Enslin, John Taggart, and so forth – who show both poets' influence. There were lots of poets who knew both Olson and Zukofsky personally: Johnson, Creeley, Duncan, Jonathan Williams, and so forth. (To my knowledge the two men themselves never met, though Olson once phoned Brooklyn to offer LZ a job at Black Mountain College.)

I wonder how it plays out these days, 35 years after Olson's death, and 27 after Zukofsky's? The personal element – so important especially for Olson-followers, many of whom were converted by what everybody testifies to as the man's magnetic and impressive pedagogy and conversation – has by now subsides. There are no poets in the 40-and-under range who had any significant personal association with either CO or LZ, I think it's safe to say. But both The Maximus Poems and "A" remain in print, and one hears about them being read...

My own academic investment, it's safe to say, has mostly been with LZ – which doesn't mean that I somehow own stock in the man, or believe that he's necessarily "more important" than Olson – and I'm interested in the movement of the academic markets. Olson's been pretty lucky for a late twentieth-century American poet. By my count, there are at least eleven critical studies of his work out there (including a biography & a memoir); his poetry has been given careful editorial attention and has been published in really nice editions; and (counting the ongoing Creeley/Olson correspondence, which is at, what? eleven volumes) there have been at least fifteen volumes of his letters printed. All that really puts LZ-related publishing activity in the dust.

How much is an aftereffect of the two men's personalities? Olson, bold and big, making sweeping statements about the metaphysical fortunes of Western Man and attracting followers to him like lawyers to a Florida fender-bender; Zukofsky, withdrawn and passive-aggressive, training a jeweller's eye upon the minute machinings of his tiny, impacted lines.

In forty years' time, it's safe to say, there won't be anyone left alive to testify to whatever personal bardic attraction either poet had. And then we'll be able to see whether young poets regard them like Pound & Williams regarded Byron and Shelley – two different aspects of something that they desperately wanted to get past – or whether they'll be able to harmonize the Minimalist and The Maximus into some new mode as yet undreamt of.

Saturday, July 30, 2005

Friday, July 29, 2005

Ronald Johnson: Radi Os

I am by turns making my first serious pass thru The Maximus Poems – that is, reading them all in a relatively concentrated period of time, with Butterick’s Guide and a stack of other critical works at hand – and savoring Flood Editions’ new edition of Ronald Johnson’s Radi Os, one of the great formative works of my largely misspent youth. The folks at Flood, in particular Jeff Clark of Quemadura, the designer, have done a wonderful job. (My only quibble in the Gothic title type, to which I think I’m just genetically allergic.) The book’s just a skoche bigger than the 1977 Sand Dollar edition, which I gather was set directly from the 1892 Paradise Lost from which RJ “excavated” his poem. Clark’s digitally reset the whole thing, preserving all of the spacings beautifully, and adding (wonder of wonders) page numbers, a very useful thing indeed.

I am by turns making my first serious pass thru The Maximus Poems – that is, reading them all in a relatively concentrated period of time, with Butterick’s Guide and a stack of other critical works at hand – and savoring Flood Editions’ new edition of Ronald Johnson’s Radi Os, one of the great formative works of my largely misspent youth. The folks at Flood, in particular Jeff Clark of Quemadura, the designer, have done a wonderful job. (My only quibble in the Gothic title type, to which I think I’m just genetically allergic.) The book’s just a skoche bigger than the 1977 Sand Dollar edition, which I gather was set directly from the 1892 Paradise Lost from which RJ “excavated” his poem. Clark’s digitally reset the whole thing, preserving all of the spacings beautifully, and adding (wonder of wonders) page numbers, a very useful thing indeed.I wasn’t sure how I felt about the new typeface – I don’t know from typefaces, but this rather anonymous contemporary face initially made me kind of nostalgic for the clearly archaic typeface of the 1977 Radi Os; then I decided that I liked it, especially to the extent that it worked to jimmy RJ’s poem away from its default description: “contemporary poem ‘composed’ by erasing words from the 1st 4 books of Milton’s Paradise Lost.” There’s no getting around the fact that RJ made his own poem out of Milton’s words, in Milton’s order, and in an 1892 typesetting, but the 2005 typeface helps to draw one’s attention from the historical aspects of RJ’s borrowings and place it more where it belongs – with the fact of Radi Os as a poem of the late 20th century.

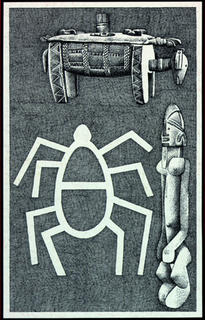

There has always stuck in my mind a phrase from Ron Silliman’s review of the first Radi Os in Eliot Weinberger’s Montemora, something about RJ’s choice of source texts being too “literary,” too obvious. Which of course brings to mind the other text that always gets invoked when one talks about Radi Os – British artist Tom Phillips’s A Humument (“quoted” above). I love Phillips’s work (anybody notice that he did the covers for Eno’s Another Green World and King Crimson’s Starless and Bible Black?) early and late, and especially A Humument, which is based on a Victorian novel, A Human Document, by a chap named Mallock. What’s most striking is that in contrast to Radi Os, where the words stand alone on Johnson’s page, floating in a sea of white, Phillips paints or draws over every page of Mallock, so that the clusters of words he preserves from his source text become only one element in a rich visual mixture. And well they might: for all the humor and whimsy TP can generate from A Human Document, he’s hard pressed indeed to come up with sorts of lyricism and sublimity that Johnson can get out of Milton. Yes, trying to extract a sublime poem out of Paradise Lost is like shooting fish in a barrel (LZ did it in “A” in about a half-dozen pages) – but choosing your source texts is about as key an operation in a “contingent” poetics as choosing the words you want to preserve from them. I suspect RJ could have pulled a poem about the eye, the mind, and the universe off of the back of a carton of Wheaties, but by opting to do Milton he both made his sublimity-work a heck of a lot easier and positioned himself in a long line of prestigious Milton-interpreters from Blake on. (Guy Davenport says much of what needs to be said there in his afterword.) Go buy the book – and pick up a copy of the latest Humument edition, while you’re at it.

[I begin to tremble – the first thing I did after reading Radi Os back in the day was to start doing my own Johnsonizing of Emerson’s Nature. In the last few months I’ve gotten a few whiffs on the blogosphere – and not the “post-avant” blogosphere – of folks starting to “Radi-o-ize” texts as something of a Creative Writing exercise. God forbid! Excavating texts becomes a workshop exercise on the level of “write a sestina with the first six words that catch your eye” or “write a poem in the voice of…” or any damn thing to do with a villanelle or pantoum.]

Wednesday, July 27, 2005

Mozart’s Hyundai

Kasey's right, of course – the car metaphor’s a pretty weak one, or at least (like everything else) gets more and more complicated as you spin it out. When it comes to automobiles, almost any evaluative metric you use is going to be tied up with class and status (not to mention sex and aggressivity and all the other things the American driver invests her/his car with); but that doesn’t mean one should necessarily dismiss those metrics. The Volvo might be the ultimate upper-middle-class Europhile Garrison Keilor-listener mobile, but I’d sure rather be in a Volvo than a Hydundai when I get T-boned by that Mustang. And a car, whether a little deuce coupe or a long white cadillac, is neither a pop song nor a poem. (Nor, usually, is a pop song a poem, tho one can occasionally apply some of the same interpretive and evaluative measures to the words.)

And’s he right that SF/J, while he may be on a bender against the term “disposable” on the blog – “So: ‘disposability’ is a useless metric, a dumbass way of discussing music” – doesn’t take anywhere near that raging stand against that implicit metric in his actual criticism. I think what he was largely grousing about was a kind of knee-jerk dismissive use of the term, which usually does have a lot of class baggage: you like that disposable crap like Beyonce, while I like timeless shit like Mozart (which I listen to in my Rolls, while you pump out the hip-hop from those tacky massive speakers in your Hyundai).

And I like Kasey’s little sociologico-cynical analysis of how pop music gets “used” by aged squares like me (I think I’m about the same age as SF/J, but I’m not nearly as cool): “a mechanism for status-generating social displays of cultural awareness among said squares.” (Unfortunately, my circle of acquaintances is so deeply square that dropping Beyonce’s name has all the cultural impact of quoting Zizek at a Palm Beach mah-jongg party – “say what?”) I even like Kasey’s wee utopian analysis of what cultural criticism at its best might be – “a multi-depth field of formal analysis in which one may examine simultaneously aesthetic forms themselves (i.e., songs and performers) and the network of political/economic/cultural production and ideology that subtends those forms” – tho that very easily folds back into “feeling ideologically pure by thinking about stuff that one enjoys anyway.”

Yeah, it’s probably too early to start thinking about long-range “durability” in regards to pop music. The best one can do is finger the songs and artists that one can still listen to 20-25 years on. Which is a pretty individualist metric (in Joshua’s words “the anecdotal subjective accounts of individual consumers”), & for most people simply means what they were listening to at that formative 18-24-year-old moment: they play a lot of Glenn Miller, Andrews Sisters, and Elvis down here in South Florida; ten years from now, they’ll be piping The Doors into the nursing homes (probably not “The End”), in another twenty Pearl Jam and Madonna. That has nothing to do with durability, everything to do with simple familiarity. (It’s the same reason William F. Buckley always argues that Shelley is the greatest English poet, and nobody after really counts – it’s what he read back at Andover, or Exeter, or wherever.)

But I think one can see something like a metric of “durability” being constructed – as it always is – on a social, collective level in the interaction of listeners and critics: in short, in the whole process of pop music canon-formation, which looks pretty much like a speeded-up version of literary canon-formation. Look at the critical-popular fortunes of the Roxy Music principals, Bryan Ferry and Brian Eno, for instance. When I started listening to them a quarter century ago (!), Ferry was a major pop music player & Eno was an obscure experimentalist, worshipped by the critics but not exactly a household name. Hard to find his records in middle Tennessee, tho it was easy enough to get Ferry’s and the post-Eno Roxy. Now Ferry’s not exactly a has-been, but who talks about These Foolish Things or The Bride Stripped Bare? (That's the Ferry album, not the Duchamp work...) On the other hand, I can walk to the nearest mall (not a hotbed of “high” culture) and pick up the entire Eno catalogue in nice new remasters. That I think is influence at work: the fact that the whole world of electronica sees Eno as a founding parent. (The Velvets the other great example of overlooked artists proving massively influential.)

Influence isn’t exactly equivalent to durability, but I think the former is or can be an element of the latter. And in poetry or pop, there’s not always a long-term equivalence: most influential late 18th-c. poet? “Ossian” by a long shot, but he’s entirely unreadable now. The artist who exerts that kind of mesmeric influence of those who come after is thereby precisely increasing her/his chances of being read (being sold, being kept in print) for the long term.

There are no evaluative metrics that are not somehow socially grounded – and since we live in a class society, that are not entangled with class investments. But as Wittgenstein says somewhere, “the difficulty is to realize the groundlessness of our beliefs” – not in order to happily chuck them away, but in order to make socially grounded evaluations of them, and to regard them with a critical consciousness.

***

Sleepy week on the blogosphere...

And’s he right that SF/J, while he may be on a bender against the term “disposable” on the blog – “So: ‘disposability’ is a useless metric, a dumbass way of discussing music” – doesn’t take anywhere near that raging stand against that implicit metric in his actual criticism. I think what he was largely grousing about was a kind of knee-jerk dismissive use of the term, which usually does have a lot of class baggage: you like that disposable crap like Beyonce, while I like timeless shit like Mozart (which I listen to in my Rolls, while you pump out the hip-hop from those tacky massive speakers in your Hyundai).

And I like Kasey’s little sociologico-cynical analysis of how pop music gets “used” by aged squares like me (I think I’m about the same age as SF/J, but I’m not nearly as cool): “a mechanism for status-generating social displays of cultural awareness among said squares.” (Unfortunately, my circle of acquaintances is so deeply square that dropping Beyonce’s name has all the cultural impact of quoting Zizek at a Palm Beach mah-jongg party – “say what?”) I even like Kasey’s wee utopian analysis of what cultural criticism at its best might be – “a multi-depth field of formal analysis in which one may examine simultaneously aesthetic forms themselves (i.e., songs and performers) and the network of political/economic/cultural production and ideology that subtends those forms” – tho that very easily folds back into “feeling ideologically pure by thinking about stuff that one enjoys anyway.”

Yeah, it’s probably too early to start thinking about long-range “durability” in regards to pop music. The best one can do is finger the songs and artists that one can still listen to 20-25 years on. Which is a pretty individualist metric (in Joshua’s words “the anecdotal subjective accounts of individual consumers”), & for most people simply means what they were listening to at that formative 18-24-year-old moment: they play a lot of Glenn Miller, Andrews Sisters, and Elvis down here in South Florida; ten years from now, they’ll be piping The Doors into the nursing homes (probably not “The End”), in another twenty Pearl Jam and Madonna. That has nothing to do with durability, everything to do with simple familiarity. (It’s the same reason William F. Buckley always argues that Shelley is the greatest English poet, and nobody after really counts – it’s what he read back at Andover, or Exeter, or wherever.)

But I think one can see something like a metric of “durability” being constructed – as it always is – on a social, collective level in the interaction of listeners and critics: in short, in the whole process of pop music canon-formation, which looks pretty much like a speeded-up version of literary canon-formation. Look at the critical-popular fortunes of the Roxy Music principals, Bryan Ferry and Brian Eno, for instance. When I started listening to them a quarter century ago (!), Ferry was a major pop music player & Eno was an obscure experimentalist, worshipped by the critics but not exactly a household name. Hard to find his records in middle Tennessee, tho it was easy enough to get Ferry’s and the post-Eno Roxy. Now Ferry’s not exactly a has-been, but who talks about These Foolish Things or The Bride Stripped Bare? (That's the Ferry album, not the Duchamp work...) On the other hand, I can walk to the nearest mall (not a hotbed of “high” culture) and pick up the entire Eno catalogue in nice new remasters. That I think is influence at work: the fact that the whole world of electronica sees Eno as a founding parent. (The Velvets the other great example of overlooked artists proving massively influential.)

Influence isn’t exactly equivalent to durability, but I think the former is or can be an element of the latter. And in poetry or pop, there’s not always a long-term equivalence: most influential late 18th-c. poet? “Ossian” by a long shot, but he’s entirely unreadable now. The artist who exerts that kind of mesmeric influence of those who come after is thereby precisely increasing her/his chances of being read (being sold, being kept in print) for the long term.

There are no evaluative metrics that are not somehow socially grounded – and since we live in a class society, that are not entangled with class investments. But as Wittgenstein says somewhere, “the difficulty is to realize the groundlessness of our beliefs” – not in order to happily chuck them away, but in order to make socially grounded evaluations of them, and to regard them with a critical consciousness.

***

Sleepy week on the blogosphere...

Monday, July 25, 2005

Faux Faulkner

A parody worth reading: this year's winner of Hemispheres magazine's "Faux Faulkner" contest. Hemispheres is the inflight magazine of United Airlines. For some reason, this piece wasn't available in the print edition...

Sunday, July 24, 2005

Disposable Taste

Hot here, too hot to really think or move. Picked up on a coversation on Sasha Frere-Jones’s blog (by way of Kasey Mohammad). Sasha posts:

Then he posts a response by Joshua Clover:

Kasey runs with this to thinking intelligently about the concept of “disposable poetry” and the dissimilarities between the poetry and pop music fields (I can’t quote, because the lucky bastard seems to have exceeded his bandwidth). Me, I’m struck by the original exchange, in its original context, and how both Sasha and Joshua (poets themselves) have to scramble to avoid this “Adornian error” of supposing that the systematic presumption of disposability in pop music somehow “makes lesser music.” (Makes music “lesser,” presumably, than the Mahler or Beethoven or Webern Adorno wd/ beat the drum for.) Okay – we all know that Adorno was a deep-dyed snob, and hated jazz, and probably would have puked if he’d seen Elvis (paraphrasing Greil Marcus), and generally had no hope of any ideologically or aesthetically positive productions arising out of either the culture industry or folk traditions.

But I’m uncomfortable, even when talking about the broad range of “pop” musics, with entirely discarding the category of disposability as an evaluative “metric.” Yes, sometimes evoking disposability does enforce “a certain set of class values.” But is it wholly a “class value” to say that a Rolls is a better car than a Hyundai? Sure, it costs about 50 times as much, and probably 75% of that overage is accounted for by pure status symbol markup: but the Rolls will outperform the Hyundai in any most any category you name – engineering, durability, handling, fit & finish, etc. (everything except, significantly, price and fuel efficiency).

Pop music is cultural production caught up in the deepest and most pernicious coils of the culture industry, where rapid production, consumption, and disposability are the absolute orders of the day. (And of course for SF/J to take disposability as an automatic perjorative would be professional suicide in some sense, since he’s after all a pop music critic.) But the impulse to make something that persists, that’s precisely durable – from Horace thru Shakespeare’s sonnets, from the Lascaux cave paintings thru Basquiat – is an awfully deeply-rooted one, and durability is a measure of evaluation that predates the culture industry – not to mention capitalism itself, and feudalism before it. I want to think about this more, but for the nonce I don’t think I can sign on to SF/J’s or Joshua’s refusal to let the marks of industry imposed sell-by dates influence their assessments of musics. For my money, it’s precisely the extent to which a given pop song or album consciously or unconsciously subverts that “disposability” that makes me value it. And that’s not just a subjective reaction, but something conditioned by social history and objective conditions of reception.

Gosh, it’s muggy here; maybe muggy enough to lead to circular thinking…

on the earbuds:

Elliott Sharp, Nots

incoming:

John Wilkinson, Effigies Against the Light and Contrivances

Vernon Frazer, Improvisations (BIG book!)

Thinking, while watching ESPN (sort of) of the uselessness of “disposability” as a critical concept: your Sudafed is my crystal meth. How do you know when my song’s run dry? How does any type of music signal disposability? Don’t long, baggy, story songs [he’s thinking Dylan’s “Hurricane”], even ones you like , present more like one-use items to you, like long, baggy novels that you enjoyed but will never read again [ie Franzen’s The Corrections]? Maybe I want to feel like “Chewing Gum” EVERY FUCKING DAY. So why would I dispose of it? I’M NOT DONE WITH IT. This axiom obviously applies equally in reverse, in every direction. If you never, ever get tired of “Hurricane,” then it isn’t disposable. So: “disposability” is a useless metric, a dumbass way of discussing music. It would be more useful—if this is what you meant—to say, “I got quickly bored of the song,” because who can argue with your experience?

Then he posts a response by Joshua Clover:

As you will surely know long before I say it, the concept "disposability" is disastrous indeed, if it comes prepackaged with valuative payload, aesthetically or worse, morally. …. when durability is taken as a positive value in pop music, that's one of the veiled enforcements of a certain set of class values. I drive a Rolls, you drive a Hyundai, punk…

But the promise that "disposability" can't somehow be recognized and thought about seems not quite right to me. To believe such a thing requires the very move you make: the suggestion that disposability is purely related to consumer experience. Whah? If I decide to save my plastic coke bottle and use it to water my plants for three years, I totally can—but this doesn't suddenly make plastic coke bottles something else. The bottle is still "disposable," in the sense that it's produced and distributed within a system that presumes its disposability, and continues to make and distribute with that presumption, and this making and distributing continues to have manifold effects on price structures, labor structures, on how the bottle looks and how it acts, etc.

This is true of pop music too. The way it's made presumes a certain duration of "use" by the consumer, and that remains a force shaping the music. Again, it's not a value issue—to assume this set of forces makes lesser music is the Adornian error exactly. But there's a way to get past that error without acceding to a set of critical terms which measure only the anecdotal subjective accounts of individual consumers...a strategy which leads to the absolute end of criticism.

"Who are you too say it's sexist? That's a useless metric, because I didn't feel it was sexist..."

Kasey runs with this to thinking intelligently about the concept of “disposable poetry” and the dissimilarities between the poetry and pop music fields (I can’t quote, because the lucky bastard seems to have exceeded his bandwidth). Me, I’m struck by the original exchange, in its original context, and how both Sasha and Joshua (poets themselves) have to scramble to avoid this “Adornian error” of supposing that the systematic presumption of disposability in pop music somehow “makes lesser music.” (Makes music “lesser,” presumably, than the Mahler or Beethoven or Webern Adorno wd/ beat the drum for.) Okay – we all know that Adorno was a deep-dyed snob, and hated jazz, and probably would have puked if he’d seen Elvis (paraphrasing Greil Marcus), and generally had no hope of any ideologically or aesthetically positive productions arising out of either the culture industry or folk traditions.

But I’m uncomfortable, even when talking about the broad range of “pop” musics, with entirely discarding the category of disposability as an evaluative “metric.” Yes, sometimes evoking disposability does enforce “a certain set of class values.” But is it wholly a “class value” to say that a Rolls is a better car than a Hyundai? Sure, it costs about 50 times as much, and probably 75% of that overage is accounted for by pure status symbol markup: but the Rolls will outperform the Hyundai in any most any category you name – engineering, durability, handling, fit & finish, etc. (everything except, significantly, price and fuel efficiency).

Pop music is cultural production caught up in the deepest and most pernicious coils of the culture industry, where rapid production, consumption, and disposability are the absolute orders of the day. (And of course for SF/J to take disposability as an automatic perjorative would be professional suicide in some sense, since he’s after all a pop music critic.) But the impulse to make something that persists, that’s precisely durable – from Horace thru Shakespeare’s sonnets, from the Lascaux cave paintings thru Basquiat – is an awfully deeply-rooted one, and durability is a measure of evaluation that predates the culture industry – not to mention capitalism itself, and feudalism before it. I want to think about this more, but for the nonce I don’t think I can sign on to SF/J’s or Joshua’s refusal to let the marks of industry imposed sell-by dates influence their assessments of musics. For my money, it’s precisely the extent to which a given pop song or album consciously or unconsciously subverts that “disposability” that makes me value it. And that’s not just a subjective reaction, but something conditioned by social history and objective conditions of reception.

Gosh, it’s muggy here; maybe muggy enough to lead to circular thinking…

on the earbuds:

Elliott Sharp, Nots

incoming:

John Wilkinson, Effigies Against the Light and Contrivances

Vernon Frazer, Improvisations (BIG book!)

Wednesday, July 20, 2005

Harry Potter & "Intelligent Design"

The results of the Guardian's "rewrite the ending of the new Harry Potter in the style of a famous author" contest are in, and just go to show that pastiche (pace Fredric Jameson) is harder than it looks. The Irvine Welsh and Dan Brown entries are quite funny, tho.

***

Here's an open letter to the Kansas Board of Education that everybody ought to sign on to.

***

And check out Charles Bernstein invoking Adorno to the Times in re/ his and Brian Ferneyhough's Walter Benjamin opera.

***

Here's an open letter to the Kansas Board of Education that everybody ought to sign on to.

***

And check out Charles Bernstein invoking Adorno to the Times in re/ his and Brian Ferneyhough's Walter Benjamin opera.

Monday, July 18, 2005

Logue-ocentrism

Pulled down my Logue books and discovered a copy of his first US volume, Songs (McDowell, Oblensky, 1959). Some fantastic ballads in here. This one riffs off of "Tom o' Bedlam's Song," which gets quoted in King Lear and which Harold Bloom is liable to affectingly recite at the drop of a hat:

And this one troubles my sleep:

The Song of Mad Tom's Dog

Once I dreamed and O I

Dreamed – hens dream of millet –

That I ate a mutton leg

Sweetened by much dancing,

One fat bone within it, yes,

One fat bone within it.

And to smell my dreamy

Bone's creaming marrow split

Promised better – lick for lick –

Than my truly wedded bitch;

So much so I growled and Tom

Woke me with a kick, yes,

Woke me with a kick.

Then I had as much to say

As any witty fish except

His mouth is wet as water,

So I listened while my tongue

Lolled against the Master:

Why make yourself a dog, sir,

Just for a dreamy bone, yes,

Just for a dreamy bone.

And this one troubles my sleep:

Lullaby

Here is the guillotine,

Here its good blade,

Here is the convict,

Here is the judge and,

Here the skilled headsman.

Here is a juror,

and eleven more

sensible fellows

never in court before.

Here is the judgement,

Here is the crime,

Here is the punishment,

in our God's name

in your name and mine

go from the court-house

into the lime.

Here are three Sundays,

Here is the warden,

Here is God's spokesman,

and here, beside him,

the convict's weight

and how he will die

gleam like steel

in the hangman's blue eye.

Here is the frail throat,

Here is the knot

long as a thumb,

Here is the spring from

Here to eternity

dressed in a hood.

And be it a man

or a woman, they shit

themselves and they come

as they swing,

and their necks get as long

as a baby's arm

over the side of a pram,

as the soul goes adrift.

Here is the court-house,

Here is the hangman,

Here he is sleeping,

Here is his candle,

and the dozen true men

have provided a daughter

to comfort his slumber.

Logue-istics

In my favorite local independent bookseller today to pick up a copy of the new Harry Potter for another member of the household (tho I'll confess to having read the first 3 chapters already) (Eric, would that be a "wave" offering or a "heave" offering? – "wave," I guess, with the wands and suchlike), I finally picked up the most recent installment of Christopher Logue's "retelling" of the Iliad, All Day Permanent Red: The First Battle Scenes of Homer's Iliad Rewritten (FSG, 2003). I've always found Logue's versions compelling and very readable indeed, if not quite the revolutions in translation some people have made them out to be. This latest one, 20 pages in, is even more cinematic than War Music and Kings; I want to retitle it, "The Iliad: The Director's Cut," it has so many shooting directions.

One can be forgiven for forgetting that Logue is a pretty decent poet in his own right, even aside from his Homeric spasms. (As I say that, I realize that I have no idea whether he's ever had a book of poems published on this side of the Atlantic.) A couple from his Selected Poems (Faber, 1996): The first one shows that Logue's one of the few English-language poets who can write a Brechtian poem that doesn't sound like pastiche:

The second is a bit less mordant:

One can be forgiven for forgetting that Logue is a pretty decent poet in his own right, even aside from his Homeric spasms. (As I say that, I realize that I have no idea whether he's ever had a book of poems published on this side of the Atlantic.) A couple from his Selected Poems (Faber, 1996): The first one shows that Logue's one of the few English-language poets who can write a Brechtian poem that doesn't sound like pastiche:

The Ass's Song

In a nearby town

there lived an Ass

who in this life

(as all good asses do)

helped his master,

loved his master,

served his master,

faithfully and true.

Now the good Ass worked

the whole day through

from dawn to dusk

(and on Sundays, too)

so the master knew

as he rode to mass

God let him sit

on the perfect Ass.

When the good Ass died

and fled above

for his reward

(that all good asses have)

his master made

of his loyal hide

a whip with which

his successor was lashed.

The second is a bit less mordant:

Last night in London Airport

I saw a wooden bin

labelled UNWANTED LITERATURE

IS TO BE PLACED HEREIN.

So I wrote a poem

and popped it in.

Friday, July 15, 2005

Hegel, Adorno, & Charlotte’s Web

I don’t really know much about the compositional history of Minima Moralia, but Adorno’s “Memento” – his little compositional handbook – is the very first piece of Part II, which suggests a taking-stock, a pause to assess what writing means to him and how writing should be gone about.

Something for Bob Archambeau, crusading for a new/late modernism, to chew on there, I believe.

On the other hand, someone has finally come out and said it:

Properly written texts are like spiders’ webs: tight, concentric, transparent, well-spun and firm. They draw into themselves all the creatures of the air. Metaphors flitting hastily through them become their nourishing prey. Subject matter comes winging towards them. The soundness of a conception can be judged by whether it causes one quotation to summon another. Where thought has opened up one cell of reality, it should, without violence by the subject, penetrate the next. It proves its relation to the object as soon as other objects crystallize around it. In the light that it casts on its chosen subjects, other begin to glow. (87)

Something for Bob Archambeau, crusading for a new/late modernism, to chew on there, I believe.

On the other hand, someone has finally come out and said it:

Too many excuses have been made for abominable philosophical prose, so let us just say outright: Hegel was a horrible writer. (His contemporary Jacobi commented on an unsigned essay: “I recognize the bad style.”)

–Robert C. Solomon, In the Spirit of Hegel: A Study of G. W. F. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (New York: Oxford UP, 1983) xi.

I. M. G. D.

Among the dandy pieces of mail awaiting me are two periodicals. The first is the latest William Carlos Williams Review (25.1), containing my review of Barry Ahearn’s edition of the Louis Zukofsky/William Carlos Williams correspondence, a book well worth reading if you’re able to get past all those notes of “Sorry, Louis, we’ll have to cancel lunch next week” and “Let’s get together this Thursday…” The second is the latest Chicago Review (51.1/2), which contains a major section saluting one of my favorite poets, Christopher Middleton, along with the usual mix of interesting poetry – Elizabeth Willis, Philip Jenks, John Wilkinson, Keston Sutherland, the late Gustaf Sobin, and Camille Martin, among others – and nonfiction (Peter O’Leary on the Levertov/Duncan letters is sure to be good).

It also contains my wee set of “epitaphs” for Guy Davenport, who died of lung cancer this past January in Lexington, Kentucky, where he’d lived and taught for some forty years. Those epitaphs are my own clumsy attempt at a Davenport pastiche, in honor of Guy himself, who I think got the short end of the stick in some quarters of the blogosphere. I mean Ron Silliman’s brief notice of his passing, which boils down to “I never dug his work and suspected him of being a fascist.”

I first encountered Guy’s essays when I was an undergraduate, maybe a junior or sophomore, and my poetry professor Tom Gardner, with whom I was reading Pound and Duncan, handed me his copy of The Geography of the Imagination and said, “I think you might enjoy these essays.” To say the least. It wasn’t just that Guy seemed incapable of writing a dull sentence (as opposed to most literary critics, who are incapable of writing one that isn’t): the essays in that collection literally opened my eyes to a whole world of writers I hadn’t known existed, who never set foot on the university syllabi back in the mid-eighties. Of course he wrote eloquently on Pound, Eliot, Joyce, Eudora Welty, and most of the major modernists: but he set me to reading Ronald Johnson (I’ll wager half of those who read Johnson now came to him through Guy’s essays – back in the mid-eighties, probably 90%), Charles Olson, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Louis Zukofsky, and Jonathan Williams, looking at Pavel Tchelichev and Ralph Eugene Meatyard, listening to Charles Ives. Guy had the knack of writing about the most recondite artworks and making them seem positively seductive

I shared maybe forty or fifty hours with Guy over the course of a decade or more. My MO was simple: I’d attend the 20th Century Literature conference at the U of Louisville, then drive over to Lexington and spend a long evening in front of his fire, smoking and talking late into the night. His house was much like its photographs on his dust jackets: cozy and comfortable, packed to the rafters with books (there was a ceaseless flow of books into the place – he once told me he received an average of five books a day: review copies, inscribed tokens, whatnots), every available inch of wall space covered with paintings, photographs, drawings. He had books in every room of the house except the bathroom and the upstairs bedroom he used as a studio. (One of his studios – the garage had been converted into a lovely, Scandinavian workspace as well.) He was a lovely ranconteur, with an endless fund of anecdotes on the most out-of-the-way subjects. And of course he poured all of his knowledge into his writings.

If Guy had a governing obsession, it was freedom: that human beings should be free from oppression, from want, from prejudice, from sexual repression, from ignorance, so that they might develop into the beauty-loving creatures that they naturally are. Some of the early Marx might serve as commentary on his stories. At least one other writer, Samuel R. Delany, sees the utopian potential in Davenport’s work. In the Appendix to Return to Nevèrÿon, Delany writes, “Within what describes for me, then, an arena of almost total dispassion, Davenport brings me again and again to breath-lost awe at the beauties he manages to construct in that lucid, glimmering language field.”

Guy was a life-long Democrat, long after the South in which he grew up and lived swung to the Republican right. He had no patience with race-baiting, with anti-Semitism. (He was as philo-Semitic as any Goy I’ve ever known: one Orthodox scholar obtained a dispensation to visit Guy on the Sabbath by explaining to his rabbi that his writer friend was a true tzadik.) For better or worse, Guy was one of those readers who could habitually separate out Pound’s virtues – his peerless poetic ear, his keen eye for literary and artistic beauties across history – from his poisonous prejudices, which for Guy were simply “whacky.”

It’s perhaps a steady diet of Guy’s writing that has condemned me, for better or worse, to being a “late modernist” rather than a “post-avant” poet. (If that’s what I am – I suppose I should give it some thought. Nah.) But his writing has taught me so much, and given me so much steady pleasure, that I can’t really bring myself to regret it.

Thursday, July 14, 2005

Composition 101

Well I'm back; last night's flight delayed an hour, not because of weather, but because someone in Detroit breached security and they had to empty the whole concourse & start over. But the house wasn't flattened by a hurricane in our absence, so I guess I should be grateful.

Spent the last few days reading John Wilkinson and Hegel (looking for the elusive pleasure there). And Minima Moralia, in which I found a wonderful three-page nugget on how to write ("Memento"), which I'll probably quote most of in the next few. The bit most immediately appropriate:

I want to put that on my syllabi from now on – or better yet, tape it to the side of my computer.

Spent the last few days reading John Wilkinson and Hegel (looking for the elusive pleasure there). And Minima Moralia, in which I found a wonderful three-page nugget on how to write ("Memento"), which I'll probably quote most of in the next few. The bit most immediately appropriate:

One should never begrudge deletions. The length of a work is irrelevant, and the fear that not enough is on paper, childish. Nothing should be thought worthy to exist simply because it exists, has been written down. When several sentencees seem like variations on the same idea, they often only represent different attempts to grasp something the author has not yet mastered. Then the best formulation should be chosen and developed further. It is part of the technique of writing to be able to discard ideas, even fertile ones, if the construction demands it. Their richness and vigour will benefit other ideas at present repressed. Just as, at table, one ought not eat the last crumbs, drink the lees. Otherwise, one is suspected of poverty.

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, trans. E. F. N. Jephcott (Verson, 1974) 85

I want to put that on my syllabi from now on – or better yet, tape it to the side of my computer.

Friday, July 08, 2005

hiatus

No, we're not fleeing a glancing blow from Dennis, but will nonetheless be out of town thru the middle of next week. Culture Industry will take a break to oil its joints and sharpen its wits.

Gustaf Sobin, 1935 – 2005

Article of Faith

...would travel forever

towards those buried mirrors, what the future

so consummately withholds. 'memories,' you'd

called them: the

grey gaze in its diadem of

dark lashes

a-

lighting, at last, in the remote ovals of the

eventual. does it glow? then

glean. ripple? then

ride the

least quivering signal clear to its

deepest

ob-

fuscated source. for only the

image––'icon,' you'd called it–– withstands the

un-

remitting dispersion of the

heart's

most adamant particles. move, then, amongst

shadows. in the

pale grammar of the grasses, read the

re-

constituted facets of the otherwise

ob-

literated face. nothing

ends.

(In the Name of the Neither, 2002)

...would travel forever

towards those buried mirrors, what the future

so consummately withholds. 'memories,' you'd

called them: the

grey gaze in its diadem of

dark lashes

a-

lighting, at last, in the remote ovals of the

eventual. does it glow? then

glean. ripple? then

ride the

least quivering signal clear to its

deepest

ob-

fuscated source. for only the

image––'icon,' you'd called it–– withstands the

un-

remitting dispersion of the

heart's

most adamant particles. move, then, amongst

shadows. in the

pale grammar of the grasses, read the

re-

constituted facets of the otherwise

ob-

literated face. nothing

ends.

(In the Name of the Neither, 2002)

Horrible

London was the site of perhaps the first contemplated act of modern terrorism, the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, whose thwarting is still celebrated as Guy Fawkes Day. Fawkes had planned to blow up King James I and the Houses of Parliament, and had stored up a huge amount of gunpowder beneath the building to that purpose. John Milton wrote three Latin epigrams on the subject, and another on the inventor of gunpowder. The rebel angels employ explosive canonry in Paradise Lost 6.

John MacGowan has a thoughtful post on the rhetorics of violence on Michael Bérubé's blog.

Today, in line at Wachovia Bank, two middle-aged, white, prosperous men:

1: That's the only thing they understand – violence. You gotta talk to them in the only language they know.

2: Hit 'em hard.

1: It's a war; look how we won World War II – Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

2: But that was a sovereign nation...

1: It's the same, sorta – Islam, the whole thing, think of it as a country. If they know they'll pay, they won't even think of doing these things. Do 'em like the Israelis.

2: Or –

1: Egypt. There's no terrorism in Egypt. Mubarak's got a police state.

2: But –

1: If someone plans a terrorist act, we hit 'em hard.

2: Get their family?

1: Kill their mother – right in front of 'em. Rip 'em open, and make 'em watch. This is war.

John MacGowan has a thoughtful post on the rhetorics of violence on Michael Bérubé's blog.

Today, in line at Wachovia Bank, two middle-aged, white, prosperous men:

1: That's the only thing they understand – violence. You gotta talk to them in the only language they know.

2: Hit 'em hard.

1: It's a war; look how we won World War II – Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

2: But that was a sovereign nation...

1: It's the same, sorta – Islam, the whole thing, think of it as a country. If they know they'll pay, they won't even think of doing these things. Do 'em like the Israelis.

2: Or –

1: Egypt. There's no terrorism in Egypt. Mubarak's got a police state.

2: But –

1: If someone plans a terrorist act, we hit 'em hard.

2: Get their family?

1: Kill their mother – right in front of 'em. Rip 'em open, and make 'em watch. This is war.

Thursday, July 07, 2005

Art Bears: The Art Box

The early eighties were a period of intense music listening for me: I had emerged from my earlier infatuations with glam rock and prog rock (though I would never outgrow my taste for British folk rock), and I was in a college town where, for the first time in my life, I was listening to real “alternative” radio – back before that had become the designator for yet another money-spinning pop genre – and had access to some good record stores, places that carried the tiny labels, the imports. One of my finds, must have been 1983 or 1984, was Hopes & Fears, a record by Art Bears, a band of which I knew nothing except the name of the guitarist – Fred Frith – who’d played a bit on some of my Eno albums.

It was about that time that, in the middle of a road trip between college and home, I ducked into a Knoxville record store and found the big Brian Eno box set, Working Backwards, which collected all of his LPs to date and added an additional unreleased disc of “music for films.” They wouldn’t take my check, I remember – I had to borrow the cash from a woman riding with me. It was the beginning of a long love affair with sumptuously packaged box sets, which in some ways culminated Christmas before last with the present to end all presents (from Herself): The Art Box, six CDs of Arts Bears music, sensitively remastered and sumptuously packaged under the direction of Chris Cutler, the band’s drummer.

Art Bears took their name from a sentence in Jane Harrison’s Art and Ritual: “even today, when individualism is rampant, art bears traces of its collective, social origin.” That’s a perhaps pretentious mouthful for a “rock” band, and in sharp contrast to the name of the band out of which Art Bears sprang, Henry Cow. Henry Cow was one of the mainstays of the 1970s British “progressive” scene, a group of viciously talented ultra-leftists who began as something like a Pink Floyd knockoff, for a while merged with the song-based band Slapp Happy (Peter Blegvad and Dagmar Krause), and then moved towards long, free-form improvisation. Hopes & Fears was initially to be the fifth Henry Cow album, this one emphasizing song forms rather than instrumentals, with Frith and Cutler mostly at the helm. By the time the record was 3/4 done, the other band members had decided it really wasn’t a Henry Cow record at all, and left Frith, Cutler, and singer Krause to finish things off.

They made two more records after 1978’s Hopes & Fears: Winter Songs (1979) and The World as It Is Today (1981). (That last is a short one – the LP plays at 45 rpm, which makes for grand sound quality but short playtime.) All three have been out of print for ages, and the earlier CD re-releases were of spotty sound quality. The music is composed by Frith, who is one of the great talents of his generation: A fantastic guitarist, making use of various Cageian “treatments,” and generally regarding the guitar in the same “outside” manner that one expects from Eugene Chadbourne or Elliott Sharp in his weirder moments. Frith is also a first-rate bassist (check him out on the Naked City records), a passable violinist, and knows his way around all manner of keyboards. His compositions, while they bear some traces of his own beginnings in the folk clubs, are like nothing else in “popular music”: his sense of melody and harmony owe almost nothing to blues-based rock idioms, but seem to spring out of some warped post-Schoenberg school of lieder.

Cutler is a fantastic drummer, harnessing a kind of Keith Moon-like anarchic impulse to a tight sense of timing and an impeccable ear for unconventional sounds. But in the Art Bears context of songs rather than instrumentals (though there are some snazzy warped folk-dances on Hopes & Fears), his gifts as a lyricist are every bit as important as his drumming. The songs on Hopes & Fears are a mixed bag of lyrics treating issues of family, generational conflict, and society. Winter Songs are based on carvings and decorations on the Cathedral at Amiens, and use those tiny fragments to build up complex meditations on history and change. “Gold,” based on wee illustration of a chest of coins, reworks a passage from Das Kapital:

I was born in the Earth

Out of fire and flood

Owned men mined me

And out of their lives all

my value derives

And out of their deaths

My authority

For

I am the shadow: Money

I come between;

Both time and persons

I disconnect

I can transform

Anything into what

I am.

And make men immortal.

Of course the lyrics alone can give no indication of how powerful this is listened to, from the quiet, melodic beginning – Dagmar Krause double-tracked in harmony over a muted piano – to the tightly restrained antipathetic energy of the second half. "Gold" is pretty much a piano song, but more often than not Krause’s glass-cutting voice, sometimes sounding like she was recorded in a broom closet, at other times with its edges blurred by fuzz effects, soars over Frith’s brutal guitar and Cutler’s assymmetrical drumming. Krause’s singing – a cross between Lotte Lenya and Yoko Ono – is an acquired taste; while she’s always on key, the timbre of the voice can be as grating as Cutler’s drums. She’s a masterful Brecht interpreter; it’s worth one’s trouble to track down Supply and Demand, her collection of mostly political Brecht songs. (Hopes & Fears opens with “On Suicide,” a haunting Brecht/Eisler ditty.)

The World as It Is Today is perhaps the most powerful political record I know before Gang of Four’s Entertainment. (Okay, maybe it ties with Sly and the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Going On.) The titles alone give an indication: “The Song of Investment Capital Overseas”; “FREEDOM (Armed) PEACE”; “The Song of the Dignity of Labour under Capital.” The lyrics here are firmly within the mainstream of English leftism, from the Levellers through the Chartists and William Morris down to Christopher Hill, and they mingle Marx with the apocalyptic visions of the Revelation of St. John the Divine. The music is appropriately apocalyptic as well: what if rock music had emerged, not out of the matrix of African American and American hillbilly traditions, but from a meeting of English folk dance, Olivier Messiaen, and Karlheiz Stockhausen?

The Art Box repackages all three of these records is glisteningly fine sound, and adds three additional CDs: Art Bears Revisited is a 2-disc set of remixes by such luminaries as Frith, Cutler, The Residents, Anne Gosfeld, and Christian Marclay, throwing in three Art Bears rarities. Art Bears provides a few more remixes, as well four tracks of the Art Bears playing live and two further performances of AB songs by various combinations of the band’s principals. I’m not a big remix fan, but these 3 discs are all well worth listening to.

The Art Box (as well as the individual Art Bears albums) is available from the ReR Megacorp website: go ahead, give it a listen. You won’t be bored.

D'oh!

Well, I guess I should have backed up the Palm Pilot. Anyway, the data's all gone, and I'm less worried about the notes of whom I've lent which books to (tho somebody's still got Houston Baker on modernism and the Harlem Renaissance) than about the address book, which has gone from a Dickensian crowd of heart-warming eccentrics to a Beckett-like blank space. I'd appreciate y'all backchannelling me contact information (addresses, phone numbers, etc.) so that I can start rebuilding. You know who you are.

Tuesday, July 05, 2005

For Independence Day, from the Irish Diaspora

[I]t is an elementary rule of warfare that you must understand your enemy if you are to defeat him; so one would have thought that sheer naked self-interest, to which the current United States government is scarcely a stranger, might have inspired it and its supporters to work out, as the saying goes, 'Why they hate us so much'. It is, to be sure, a signal advance in intellectual enlightenment for some Americans that this question has even occurred to them. It is a pity that it took an appalling tragedy for them to wake up to the fact that not everyone enjoys being hectored about democracy by a nation with a fraudulently elected president, as well as with an electoral system which means that you need to have the financial resources to buy up Niger, Chad, the Cameroons and the Central African Republic if you are to become a democratic representative of the popular will. (Perhaps some enterprising US businessman will get round to this in the fullness of time.)

Not everyone, either, relishes being lectured about freedom by an American political establishment for which such freedom means lending military and material support to a whole range of squalid right-wing dictatorships throughout the world, while maiming and destroying the citizens of other regimes which dare to threaten its own geopolitical dominance, and thus its profits. One is not over-impressed by governments which prate of human rights and announce that the prisoners whom they are busy torturing in the Cuban concentration camp are 'bad' even before they have been put on trial. The desire to rule the world used to be considered the paranoid fantasy of sad, emotionally retarded men with inadequate love lives and dandruff on the shoulders of their jackets. Nowadays, it is the declared aim of a nation which regards itself as God's gift to anti-imperialism.

–Terry Eagleton, After Theory (Basic Books, 2003) 224-5

Not everyone, either, relishes being lectured about freedom by an American political establishment for which such freedom means lending military and material support to a whole range of squalid right-wing dictatorships throughout the world, while maiming and destroying the citizens of other regimes which dare to threaten its own geopolitical dominance, and thus its profits. One is not over-impressed by governments which prate of human rights and announce that the prisoners whom they are busy torturing in the Cuban concentration camp are 'bad' even before they have been put on trial. The desire to rule the world used to be considered the paranoid fantasy of sad, emotionally retarded men with inadequate love lives and dandruff on the shoulders of their jackets. Nowadays, it is the declared aim of a nation which regards itself as God's gift to anti-imperialism.

–Terry Eagleton, After Theory (Basic Books, 2003) 224-5

Monday, July 04, 2005

Lorenzo Thomas, 1944 - 2005

Sugar Hill

How you like that?

Quadrasonic baby

When you turn these speakers up

Behind this music

A breeze actually blows

Through the room. Man!

That's how come I believe engineers

Truly exist

Though we cannot see them

(The Bathers, 1981)

How you like that?

Quadrasonic baby

When you turn these speakers up

Behind this music

A breeze actually blows

Through the room. Man!

That's how come I believe engineers

Truly exist

Though we cannot see them

(The Bathers, 1981)

Friday, July 01, 2005

Olson & Larkin

Ron asks “Which 3 poems did Creeley omit from In Cold Hell, In Thicket?” Good question, and one which took me – with copies of Olson’s Collected Poems, Archaeologist of Morning, The Distances, Selected Writings, and about a dozen volumes of letters and prose works (not to mention about three-quarters of the published Olson commentaries) – the better part of an hour to figure out. Originally, In Cold Hell was to be published as an issue of Cid Corman’s Origin, and ended up being printed by Creeley’s Divers Press after some sort of snafu. In a letter to Corman of 4/5 December 1952, Olson sends a complete proposed contents for In Cold Hell. The three poems that didn’t make it into the Divers edition, so far as I can tell, are: “A Po-sy, A Po-sy,” “A Discrete Gloss,” and “To Gerhardt, There, Among Europe’s Things of Which He Has Written Us in His ‘Brief an Creeley und Olson.” Creeley also seems to have altered Olson’s proposed ordering of the remaining poems. But since Butterick’s Collected Poems doesn’t include a contents page for In Cold Hell, In Thicket, I can’t tell how much. Hence part of my frustration with this otherwise lovely edition.

How about this one?:

***

An analogous case, brought to me by the mailman the other week: Anthony Thwaite’s new version of Philip Larkin’s Collected Poems (FSG, 2003). (This a “desk copy,” since I made a resolution years ago that I was never going to pay for a Larkin book.) Thwaite issued a Larkin Collected Poems in 1988 that presented everything in chronological order of composition, but apparently there was so much kvetching about this – or maybe Faber & FSG just saw an opportunity to squeeze a bit more money out of the Larkin cash cow before the market sinks – that he’s reissued pretty much the same poems, this time organized as they were in PL’s published collections.

I can’t say I have much time for Larkin (tho it’s always fun to quote “This Be the Verse” at a stuffy cocktail party – “They fuck you up, your mum and dad…”), but this one, composed when PL was about 21, caught my eye:

On the earbuds:

John Zorn, IAO: Music in Sacred Light and String Quartets

How about this one?:

One Word as the Complete Poem

dictic

***

An analogous case, brought to me by the mailman the other week: Anthony Thwaite’s new version of Philip Larkin’s Collected Poems (FSG, 2003). (This a “desk copy,” since I made a resolution years ago that I was never going to pay for a Larkin book.) Thwaite issued a Larkin Collected Poems in 1988 that presented everything in chronological order of composition, but apparently there was so much kvetching about this – or maybe Faber & FSG just saw an opportunity to squeeze a bit more money out of the Larkin cash cow before the market sinks – that he’s reissued pretty much the same poems, this time organized as they were in PL’s published collections.

I can’t say I have much time for Larkin (tho it’s always fun to quote “This Be the Verse” at a stuffy cocktail party – “They fuck you up, your mum and dad…”), but this one, composed when PL was about 21, caught my eye:

Mythological Introduction

A white girl lay on the grass

With her arms held out for love;

Her goldbrown hair fell down her face,

And her two lips move:

See, I am the whitest cloud that strays

Through a deep sky:

I am your senses’ crossroads,

Where the four seasons lie.

She rose up in the middle of the lawn

And spread her arms wide;

And the webbed earth where she had lain

Had eaten away her side.

On the earbuds:

John Zorn, IAO: Music in Sacred Light and String Quartets

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)